This collection of Civil War Letters by Benjamin Franklin Hulburd was purchased by an acquaintance of mine who asked me to transcribe them, research the contents, and preserve the material for the benefit of historians and family history researchers on this website. I welcome your comments and would be delighted if you could share additional material that would enhance the collection.

Who was Benjamin Franklin Hulburd?

Benjamin Franklin Hulburd (1822-1864) was the youngest son of William Hulburd (1774-1846) and Susan Conger (1784-1860) of Waterville — an isolated village just 25 miles or so south of the Canadian border in the heavily wooded, mountainous and scenic region of Vermont. Residents here, in the days long before tourism created a viable industry, were hard-pressed to make a living. Subsistence farming predominated.

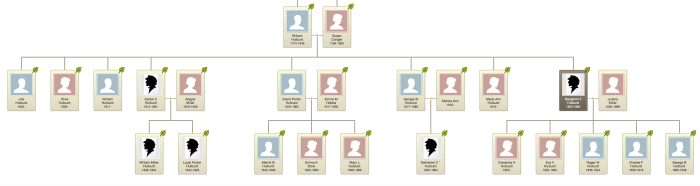

Sometime just before 1850, Benjamin married Juliana Miller (1830-1898) who became his helpmate about the farm and together they raised five children — Cresentia (b. 1850 but died before the Civil War), Eva (b. 1854), Roger (b. 1856), Charles (b. 1859), and George (b. 1863). All of Benjamin’s letters included in this collection were written to his wife and their children’s names are naturally mentioned frequently, as well as a few other extended family names. The following abbreviated family tree was created in Ancestry.com for the purpose of illustrating the family relationships of the principal people mentioned in these letters.

When the Civil War erupted in 1861, Benjamin was already nearly 40 years old. This advanced age did not prevent him from offering his services as a soldier, however. And though a patriot, Benjamin’s motivation for leaving his family and risking his life seems to have been primarily driven by financial need — an opportunity to earn double the income he would have earned by remaining home on the farm.

Many of the men who enlisted initially in 1861 from this area of Vermont became members of the 2nd Vermont Infantry. This included Benjamin’s brother, Daniel C. Hulburd (1813-1881), and his nephew, Loyal Porter Hulburd (1844-1929). They were members of Company H. Though he may have wished to join the 2nd Vermont too, Benjamin resisted the temptation to go. Perhaps he thought the war would be over soon enough and that his wife and young family needed him at home. But the war dragged on beyond everyone’s expectations, and when more men from this region were recruited in March 1862, Benjamin joined the next wave of volunteers who were mustered into the 7th or 8th Vermont Regiments for three years service.

It was Benjamin’s misfortune to be placed in the 7th Vermont which came to be known as the “hard luck” regiment. Nothing, it seems, ever went their way and the regiment lost nearly half its members from disease against only 13 battle casualties. The first two chapters of this collection — “With a good face” and “Worse cases than mine” contain the letters Benjamin wrote while serving with the 7th Vermont. The letters take the reader from New York Harbor to Ship Island (off the gulf coast of Mississippi), to New Orleans, and to Pensacola where Benjamin was discharged for disability sometime early in 1863 after only about one year of service.

From his letters we know that Benjamin returned to his family in time for spring planting in 1863 and that he worked on his farm all year until very late in 1863 when he offered his services to the country again, this time re-enlisting to fill the ranks of the 2nd Vermont Infantry. He joined them in winter camp at Brandy’s Station, Virginia, in January 1864 and was with them through the series of battles that came to be known at Grant’s Overland Campaign in the spring and summer of 1864. The final two chapters of this collection — “A masterly stroke somewhere” and “Till they slip out again” — contain the letters Benjamin wrote while serving with the 2nd Vermont.

Benjamin was with the 2nd Vermont (part of Wright’s 6th Corps) when they were sent post haste from City Point, Virginia, back to the Nation’s capitol to prevent Confederate Gen. Jubal Early’s men from seizing the city. After that threat was thwarted, the men of the 2nd Vermont participated in Sheridan’s Shenandoah Valley Campaign and it was during the Battle of Cedar Creek on 19 October 1864 that Benjamin was killed.

Benjamin’s Civil War letters are a delight to read and add rich insight to the service of the boys in both the 7th and the 2nd Vermont Regiments. Benjamin’s advanced age offers a more mature perspective on the war than is normally encountered in the letters of a private.